“Hey, that’s a really nice outfit,” I told a friend when we met for dinner. She smiled and said it was from a platform that sold handcrafted, sustainably made clothing. Curious, I looked it up later—the outfit cost ₹6,500. I didn’t flinch. If anything, my admiration for the brand grew.

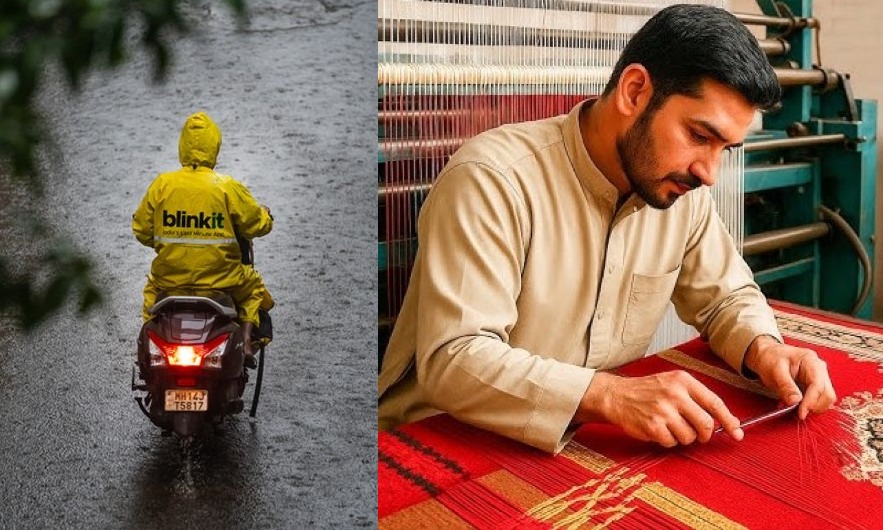

Earlier that same day, I had ordered groceries through a quick commerce app. When prompted to tip the delivery partner, I declined. An hour later, I ordered handcrafted décor for my home and once again paid a visible premium, without hesitation.

The contrast bothered me. It forced me to confront a quiet hypocrisy in how I—and many of us—decide what labour is worth.

That discomfort showed up publicly on New Year’s Eve, when the founder of a large Indian quick commerce company (its name rhymes with Tomato) posted a series of tweets defending the gig economy. He argued that gig work provided livelihoods to many unemployed, unskilled Indians and implied that rewarding gig workers through tips was the customer’s responsibility, not the company’s. This came on the same day gig workers had tried, unsuccessfully, to strike for better pay and working conditions.

The reactions were polarised. Some praised the founder for being honest. Others felt he was deflecting blame by moving responsibility away from platform economics and placing it on individual consumers.

All of this led me to a simple question: why are we comfortable paying a premium for handcrafted or customised products, but hesitant to extend the same generosity to gig workers—whose effort is often greater and far more visible?

Part of the answer lies in how we think about different kinds of work.

Handcrafted products aren’t just seen as skill-heavy. They’re seen as intentional. Someone made a choice, added a personal touch, and left behind a sense of authorship. Branding, storytelling, and the language of craft make that technique visible.

Gig work, on the other hand, is seen as task execution. Even when it involves navigating traffic, rain, unsafe roads, and restrictive housing rules, the work is framed as operational rather than creative. The bias is subtle but real: we reward visible agency more than raw effort.

This isn’t because we don’t notice how hard gig workers work. We do. The delivery rider in the rain is right in front of us. What reduces the perceived value is repetition. When effort is repeated every day, it becomes routine. What is routine, becomes expected. And what is expected struggles to command a premium.

Handcrafted labour escapes this because it is framed as exceptional, not routine. Its effort is not just visible—it is presented as scarce.

Behavioural psychology explains part of why we hesitate to tip, but economics matters just as much.

Paying more for a handcrafted product feels like a clean transaction. Tipping, however, carries discomfort. It reminds us of inequality. It forces us to judge who deserves what. It blurs the line between generosity and obligation.

Tipping can feel like a small attempt to fix a broken system—one we didn’t create, but are being asked to compensate for. Buying a handcrafted product, in contrast, allows us to feel ethical without feeling responsible.

One tweet from the quick commerce founder added another layer to the debate. He shared a breakdown of a gig worker’s potential daily earnings, suggesting that their monthly income could match that of an entry-level employee in an Indian IT services firm. Critics of the strike jumped on this, asking why gig workers didn’t simply find other jobs if the work was so demanding.

The comparison is revealing.

Having been a “veteran” of the IT services industry myself (a full 12 months), the similarities stand out. Entry-level IT services roles and gig work are both labour-intensive, repetitive, and underpaid. The work is process-driven, standardised, and built for scale. Individual ownership is low. Replaceability is high.

In both cases, repetition devalues labour faster than effort can redeem it.

The low pay here isn’t about low skill. It’s about low pricing power. Pricing power sits with platforms and clients, not with workers. Scale benefits companies far more than individuals.

That said, IT services employees do have one advantage that gig workers don’t: optionality. Over time, some can move up—through career ladders, skill-building, overseas roles, or better pay. Today’s low wage is often framed as the entry fee for future rewards.

But this promise isn’t evenly distributed, and it doesn’t justify being underpaid today. Much like the “flexibility” offered to gig workers instead of stable income, future mobility acts as a psychological cushion—it keeps the system running without fixing its flaws.

Another claim made by the founder was that gig work offers opportunities to uneducated citizens. This brings us to a deeper issue: class and access.

Education and social capital don’t just build skills; they signal legitimacy. Many gig workers and entry-level IT employees come from backgrounds that limit access to elite credentials, strong networks, and the ability to shape narratives. Their work enters the market already discounted.

When handcrafted work is backed by education, branding, or cultural capital, the same effort is reframed as artisanal—and therefore premium-worthy. The gap isn’t about capability. It’s about who gets to define value, and how convincingly.

The gig economy, like the Indian IT services industry, has brought income to millions of households. It has raised convenience to new levels and driven consumption. These sectors matter.

But acknowledging their impact doesn’t mean ignoring their inequalities.

Mass employment cannot be used to justify poor working conditions, low wages, or shifting moral responsibility onto consumers. These are not problems that can be solved through tipping or personal guilt. They require structural solutions.

The real question isn’t whether gig work or IT services create value. It’s why some forms of labour are allowed dignity, narrative, and premium—while others are designed to remain routine, invisible, and cheap.

That question is worth sitting with.